Knowledge of nature and its bounties has inspired works of art since the dawn of time. It led to the organic understanding of art and its forms as living entities, ever changing and producing new progeny. The “life of forms” figuratively depicts this internal functioning, which was also noticed by art historians, namely, Henri Focillon. In this concept, our world is shaped by dynamic forms that give birth to its possible shapes and metaphors. They represent the modality of human life – its sphere of potential.

Nature was not just a source of inspiration, but an analogy to artistic output and a fundamental ideal linked with the quality of natural authenticity. The inscrutable variability of nature was also a reminder of man’s limits and an acknowledgment of the natural order, which surpasses man and his intentions and provides continuity.

Nature was thus the muse of diverse, often disparate artistic movements. Some admired her inner harmony and order, others celebrated her unrestrained elements. In this way, they projected on to her the two-fold tendencies of human existence – the desire for a rational, balanced world, for the stability of a timeless order, and conversely, the will for change, spontaneous dynamics, and the enactment of all hidden potential and power. Between these ambivalences, nature became a symbol of emotionality and unbridled freedom, as well as inner tranquility and rootedness.

More text next to the photos

Wild Shapes

By abstracting the opulent formal richness of the natural world, artists endeavoured to attain the ideal essence of form and to capture its intrinsic rhythm and structure. What were initially realistic figures and objects were reduced to symbols disregarding all that was superfluous. This paring of abstraction down to symbols had accompanied art from its very inception, as is manifested, for example, in the evolution of ornamentation. In the 20th century, it gave rise to the universal visual language of modernism that was distinctive both of the visual arts and design.

Vase with a conch and corals, 1850. Thun Porcelain Factory, Klášterec nad Ohří (Klösterle an der Eger). Painted porcelain

Flowers in a Swamp

The abstract style also impacted the new studio art in which, post mid-century, free creativity flourished, unfettered by a regard for the practical functionality of objects. In the fields of glass, ceramics, jewellery and textile, artists used traditional materials in a manner that was close to the arts of sculpture and painting.

Flowers in a Swamp sofa, 1991. Bohuslav Horák (born 1954). Metal, wood, leather

Clocks

Empire clock The Horses of Diomedes, 1824. Gentilhomme Workshop, Paris. Gilt bronze

The Symbol of Fish

The motif of a fish appears frequently in works by the accomplished Viennese glass and porcelain painter Anton Kothgasser and in the creations of Bohemian glassmakers. The fish could have symbolized a tacit secret between the donor and the donee or could have suggested fulfilled wishes. The depiction of flowers represented a like coded, hidden form of conversation. The “language of flowers” of the period established the symbolic meanings of all botanical species and their colours, and became a sophisticated social pastime facilitating the expression of secret feelings. For instance, the forget-me-not could have been an appeal for a cherished memory, the rose a declaration of love, the lily stood for innocence, the holly hock denoted loyal friendship.

Beaker decorated with a goldfish, c. 1825, Anton Kothgasser (1769–1851), Vienna (painting), Bohemia (glass). Glass, cut, stained, and painted

Glass or Stone?

Inspiration in inorganic nature was amply employed in the works of the glass painter Friedrich Egermann, who achieved extraordinary status among glass decorators of the North Bohemian region. So-called lithyalin glass (from Greek lithos, “stone”), a type of glass of his invention, strongly resembled polished natural stones. During their manufacture, a stain was brushed onto the cut opaque glass surface that was then fired in the kiln, adhering to the glass body and creating a marbled effect that resembled polished semiprecious stones.

Three-part flagon, c. 1828, Friedrich Egermann (1777–1864), Bor (Haida, now Nový Bor). Lithyalin (red hyalith, cut and stained)

Souvenirs from Travels

After the end of the Napoleonic Wars, a distinctive movement developed in the arts and society in Central Europe, now referred to as Biedermeier. This style is characterized by a pursuit of harmony and pleasure in life, and an endeavour to avoid dramatic upheavals in the lives of individuals and society as a whole. Contrary to revolutionary ideologies, Biedermeier emphasized collective order, its stability and duration. Personal and family memory, and keepsakes as recollections of loved ones, the home and places visited, all served as means of encapsulating time. This memorial function was also fulfilled by commemorative glass and porcelain presented as gifts to friends or as souvenirs from travels, mostly visits to Western Bohemian spas.

Goblet and cover with vistas of Teplitz and its environs, 1835. Probably Nový Svět (Neuwelt) in the Krkonoše Mountains (glass and cut decoration) and Teplitz (engraving)

Dynamics of Movement

The Art Nouveau re-embracement of life and nature led also to the artistic exploration of the dynamics of human body movement. The theme of the human figure in motion was also reflected in ceramic production. The sculptor Ladislav Šaloun based his composition “Kiss” on the rotation of two bodies of lovers in an embrace. His model was awarded First Prize in a contest for a decorative vase announced in 1899 by the journal Volné směry (Free Directions).

Kiss vase, 1899. Ladislav Šaloun (1870–1946). Colour-patinated plaster model

Poetry

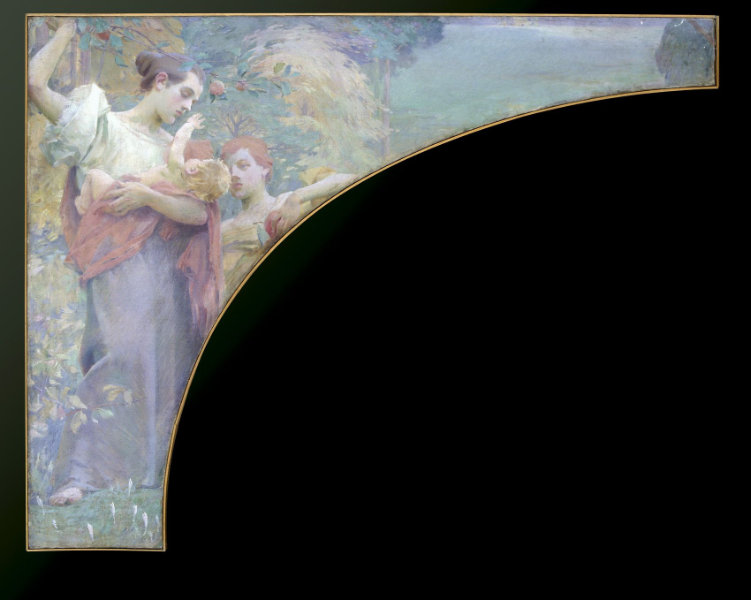

Preisler’s decorative paintings adorned the entrance to the interior that showcased the Chamber of Trade and Commerce in Prague – the founder of the Museum of Decorative Arts – at the Paris World Exposition in 1900. For the first time, Preisler painted on a larger surface his poetic idea of youth and spring, wistful daydreaming and silent harmony with the natural cycles – all motifs that he employed soon after in his following paramount works.

Jan Preisler (1872–1918), 1899: Spring (Sowing in Hope of Success. Pair of decorative paintings for the interior of the Prague Chamber of Trade and Commerce at the 1900 Paris World Exposition. Oil on canvas

The life of forms

The life of forms – if we are to understand forms as living and infinitely changing elements – necessarily leads to the crossing of all clear outlines and boundaries of shapes, to deformation and extinction. In this kaleidoscope of the visual world, apart from clear and easily discernible forms, we also encounter the phenomenon of the shapeless, the amorphous. Shapelessness need not only mean the departure from or the absence of form but is simultaneously a process of creation, of formation. From the ancient times, the lack of form has represented the inception of all things born from the primeval formless matter. It is a quest for new possibilities of form, their seed and fruit, as is implied, for example, by the title of the vase Fruit (Plod) by František Bílek.

Fruit vase, 1896–1900, František Bílek (1872–1941), Chýnov near Tábor

The Loetz glassworks

The Loetz glassworks in Klostermühle near Rejštejn in the Šumava region was one of the most avant-garde manufacturers of Art Nouveau glass in Europe. Already by the late 1880s, the production of the glassworks, founded in 1836, had been enjoying great success with its coloured marbled glass imitating semiprecious stones. From 1898 the Art Nouveau idiom came to full expression through the manufacture of vases decorated by winding softened trailing and combed threads onto the glass body. The subsequently applied iridescence endowed their surface with a rainbowlike effect. In 1900 this visually compelling glass, reminiscent of natural structures, received the Grand Prix at the 1900 Paris World Exposition.

Vase, 1902. Johann Loetz Witwe glassworks, Klášterský Mlýn (Klostermühle). Colour-layered glass, with trailing and combed threads, inlaid, hot-shaped, and iridized

Louis Majorelle

Louis Majorelle was one of the protagonists of the Art Nouveau style in Nancy, France. After taking over his father’s cabinet-making workshop, he engaged in the production of revivalist furniture. Following his acquaintance with the designer Émile Gallé, he came under the spell of the graceful vegetal forms of the Art Nouveau style. This is documented by the huge sideboard that originally formed part of a luxury dining room suite. Stylized floral intarsia, fittings and delicately carved ornaments transform into raised, sinous line designs, thus evoking a sense of dynamism. The entire set of furniture was purchased by the entrepreneur Slavoj Grégr – the son of the prominent Czech politician and journalist Julius Grégr – straight from the 1900 World Exposition in Paris.

Sideboard, 1900. Louis Majorelle (1859–1926). Produced by the Mercier Frères company, Paris; exhibited 1900 at the Paris World Exposition. Mahogany (solid wood and veneer), inlays of various woods, brass, glass

Leopold Bauer

Together with Jan Kotěra and Josef Hoffmann, the native of Krnov, Leopold Bauer, is regarded to be one of the most talented students of the Viennese architect Otto Wagner. All three were born in the Czech lands and left a major imprint on the history of modern architecture and design. Bauer’s exclusive set of furniture made for the textile manufacturer Rudolf Larisch perfectly embody the features of the early phase of Geometric Art Nouveau. Distinctive are the prismatic forms outlined by strips of delicate checkerboard inlays and complemented by posts suggestive of an inspiration in the Neoclassical style.

Bureau from a furniture suite for Rudolf Larisch in Krnov, 1900–1902. Leopold Bauer (1872–1938). Produced by J. W. Müller, Vienna. Maple, birch and exotic veneers, mother-of-pearl, brass

Jan Kotěra

The early work of Jan Kotěra, a leading figure of Czech modernism in architecture of the Fin de Siècle was derived from plant morphology that emphasized the construction principles and tectonics of natural forms. However, already in the first decade of the 20th century, Kotěra’s designs of architecture, furniture and interiors acquired a more abstract appearance; they tended towards a more pronounced rhythmization and simplication of form at which Kotěra arrived under the impact of his Viennese mentor, architect Otto Wagner.

Chair for the director’s office of the National Theatre in Prague, 1902. Jan Kotěra (1871–1923). Carved oak

Émile Gallé

The interest of Art Nouveau artists in the scientific knowledge of nature often had a deeper reason. Some were engaged in specialized studies in the field of natural sciences, such as the renowned French designer Émile Gallé, who was an accomplished botanist. His research into the botanical species of Lorraine and particularly his long-time penchant for orchids were reflected in Gallé’s glass and furniture designs.

Vase, c. 1910, Émile Gallé, Nancy, France. Opal glass, orange-shaded, overlaid with red glass, and acid-etched

Pavel Janák

Artists advocating the tenets of Cubism fully embraced the visual impact of the geometric order that alluded to the immutable laws of the physical world. Interest in the essence of material matter led the Cubist artists to emphasize structure and to express inherent structural forces not only in painting and sculpture but – in the case of Czech designers – also in the manufacture of furniture and home interior accessories, and in architecture. Typically, they had broken forms based on the decomposition of shapes and a dynamic concept of space. Chair, 1911–1912, Pavel Janák (1882–1956), design, Prague Art Workshops (PUD). Oak and walnut

Cubism

Parallel movements that strove for the geometric purity of forms, their visual restraint and the elimination of everything redundant may appear as contradictory to the Art Nouveau’s decorative floral style. However, this trend towards the simplification of form already appeared in the times of Neoclassicism and Biedermeier, and early modern art of the beginning of the 20th century consciously drew on it. Its geometric idiom shared the same conceptual roots as the Organic Art Nouveau style: both were imbued with a reformist charge and a desire for social revival and new ethical culture. The geometric style followed a path towards “the essence of form”, which was eventually also embarked upon by Czech Cubist artists and future generations of designers.

Tobacco container, 1918. Vlastislav Hofman (1884–1964), design for Artěl, Prague. Made by Antonín Štolba, Prague. Zinc sheet, copper-plated, black lines

Cubist Vases

Before the onset of World War I, the theoretical work of Pavel Janák presented the notion of the oblique surface that is analogous to morphological forces in nature and expresses the infusion of matter with a spirit of its own through the human act of creativity. The governing idea of the inherently integral form was met by the stable structure of the crystal that directly inspired many designs of Cubist artefacts.

Concave and convex vases, 1911. Pavel Janák (1882–1956), design. Graniton, Rydl & Thon, Svijany-Podolí. Made for Artěl, Prague. Creamware, glazed, painted in black and gold

Alois Metelák

By abstracting the opulent formal richness of the natural world, artists endeavoured to attain the ideal essence of form and to capture its intrinsic rhythm and structure. What were initially realistic figures and objects were reduced to symbols disregarding all that was superfluous. This paring of abstraction down to symbols had accompanied art from its very inception, as is manifested, for example, in the evolution of ornamentation. In the 20th century, it gave rise to the universal visual language of modernism that was distinctive both of the visual arts and design. The abstract style also impacted the new studio art in which, post mid-century, free creativity flourished, unfettered by a regard for the practical functionality of objects. In the fields of glass, ceramics, jewellery and textile, artists used traditional materials in a manner that was close to the arts of sculpture and painting.

Bowl, 1930, Alois Metelák (1897–1980), Made by Emilián Celler, Podmoklice. Smoky glass, cut. Fireclay coated with black graphite